- Home

- Rebecca Tinnelly

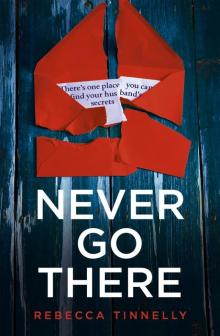

Never Go There Page 9

Never Go There Read online

Page 9

All of James’s new friends, the ones from his work at the park, were awkward, didn’t know what to do or to say, even more so since Maxwell, none of them really knowing her that well at all.

And there were no more of her own, no friends from a job or a course or a hobby. No one suitable, in James’s eyes (and, by proxy, Nuala’s). And what would she want with girlfriends who would drag her from pub to club, morals as low as their necklines, drinking and flirting and doing what most women do? What other women do? Nuala was different, special, because she had saved herself for James. She was his and his only, untouched by the dirty masses like so many other women out there. She didn’t need those women as friends. She didn’t need anyone else, and if she had to talk to someone then why not talk to James, tell him everything, because wasn’t he everything to her? Wasn’t he? Well? Because she was everything to him, and it would have killed him, killed him, if he hadn’t been everything to her.

And there was nobody she could think of to turn to. Nobody that James, dead or alive, would want her near. Her parents were both dead, her maternal family made up of strangers in Ireland, father’s parents passed before she was born. And his family was one woman only; a mother so terrible he couldn’t bear to be near her, so terrible he had changed his name, cut her off.

When she finally lifted her head, the room had gone dark, the streetlights glowing through the blinds.

Nuala walked past the bed to the other side of the room, through the door that led to the en-suite. The room stank, the smell far worse than the kitchen. The toilet hadn’t been flushed in days. Why bother to flush a toilet? What was the point?

She opened the mirrored cabinet above the sink and stared at all the bottles and packets within. Paracetamol, ibuprofen, aspirin, sleeping pills, temazepam, antihistamines, hypnotics, Prozac, Sudafed, flu tablets, codeine and a small, purple bottle with a white lid, a smiling baby on its label.

She took them all into her bedroom and emptied them, packet by packet, onto the duvet. She filled her mouth in handfuls, washing the pills down with the Calpol and let herself fall, face down, on the blood stain.

Emma

Saturday, 18th November, 2017

The side of her face still pressed to the gap in the door, she paused. Her blood ran cold, her body frozen. Except her ears, burning with the name she had heard.

James.

Nuala Greene had spoken it, the name like a whisper carrying up from the bar.

The woman was here because of James. She’d been right.

‘It’ll destroy her if she finds out.’ That was Maggie.

What would destroy her, and why? What the hell were they talking about?

Emma opened her bedroom door further, craned her neck into the dank little hallway, trying to hear more, the floorboards creaking as she stepped out.

Silence following her footfall.

‘I’ll tell you, but not here.’

Maggie was going to tell her.

Tell her everything.

After all Maggie had said to Emma that morning, urging her to forget about the stranger, telling her how harmless she was, how she had nothing whatsoever to do with James.

And now Maggie was going to tell this woman everything. Some trumped up blow-in from London was going to find out all about her past. Because Emma’s story was woven with James’s, Maggie wouldn’t be able to tell Nuala why James left the village without explaining what happened to Emma.

If only Emma had heard more of the conversation, instead of snippets when voices were raised.

She heard the front door close. In the street, there was the rumble of an engine and she moved to the window, watched Maggie climb into Nuala’s small red car, the same car that had caused all the whispers in the bar last night. She watched it drive away, following the road out of the village, the thick-necked shadow of Maggie visible in the passenger seat.

She could hear the car long after it had disappeared from view. She listened until its noise vanished, the sound lost to that of the wind, of the cows in the dairy behind them, of the crow scarer blasting off gunshots in the fields either side of Shore Road.

She needed to clean the bar up, sort out whatever Maggie had spilt downstairs. She needed to lay the fire, clean the glasses, make sure the bar was ready for service that night, needed to go to the shop and buy food. She should get to work. Take her mind off Nuala Greene, take her mind off whatever Maggie was telling her.

Her hands began to throb, the burn from the bleach stinging again.

She should get to work, carry on as normal.

But outside her bedroom, in the hallway that ran the length of the house, she couldn’t take her eyes off the guest room.

She reached for the door, pulse galloping as it opened inward.

A single bed. A sink fastened at the corner, no mirror. The wallpaper spotted with mildew, black with damp at the bottom edge. One bedside table, the drawer at the top missing and the surface covered in old cigarette burns from when Maggie used to let people smoke inside.

But she hadn’t let that happen since the fire next door, even though it was caused by a chip pan, not a fag. Even though that fire had been set on purpose.

On the floor by the foot of the bed was that Burberry bag, and Emma’s jaw clenched at the label.

Knees on the ground, the thin woollen rug protecting against the splintery wood beneath, she opened the bag and looked through it.

A small, quilted toiletry bag held tiny bottles, Clarins, Arden, Molton Brown on the labels, a gold tube of Touche Éclat.

The cashmere jumper Nuala had worn the day before. Reiss, the label read. The jeans were there too, Diesel no less, and even her underwear was by Morgan Lane.

Emma hadn’t worn anything like this since moving to the pub, since Maggie started footing the bill. Her own lovely clothes, bought by her stepmother, Elaine, from the department stores in town, were gradually replaced by supermarket own brands, the underwear in plastic packs from Primark. She still had the last cardigan Elaine had bought for her, a soft, pale-green wool. She held it to her nose sometimes. She used to be able to smell her dead stepmother’s perfume, a mixture of gardenia and clean cotton. The real scent was long gone, she just imagined it, remembered it, now, never having the money to buy it herself.

There was no perfume in Nuala’s bag, but Emma suspected that, had there been any, it would have been Chanel. Even Nuala’s socks were Bridgedale, for Christ’s sake. No holes. No worn heels.

And this woman was about to find out all about Emma’s sad little life, all about the girl James left behind.

She held Nuala’s jumper up to the daylight, the cashmere too thick to let the sun through. Emma pressed it to her body, thought what-the-hell and tried it on, pushing her head through the hole in the top and feeling the soft wool stroke her cheek.

She had forgotten how nice good wool felt.

As she hugged the fabric to her she noticed something else.

A small piece of paper on the side table.

Keeping the jumper on, her hands still stroking the front, she stepped away and picked up the paper.

An envelope.

Addressed to James.

Why would Nuala have this? And where was the letter that came with it?

What right did she have to open this when it wasn’t hers?

It was for James.

How did she get it?

An idea, like a seedling, took root in her head. The letter was addressed to James Lunglow, the name Emma had been searching for online for seven years.

Hands shaking, burns stinging, she prised her phone from her back pocket and held the handset up to the window, the top right-hand corner where sometimes she would get a bar or two of reception.

In the search bar, she began to type his name, James Lunglow automatically coming up as a suggestion. Her guts writhing, stomach weak with the horrible possibility that Nuala was his wife after all, she deleted the Lunglow, changed it to Nuala’s surname, Greene.

&n

bsp; She waited for the results to come in, hoping she was wrong, that James hadn’t forfeited Emma for this woman, with her money and nice things.

But what came up in her search was far worse.

The blue and white homepage for Facebook.

James staring back from the photo in the top corner.

And comment after comment, stretching back for six months.

We’ll miss you.

Won’t forget you.

R.I.P.

Emma dropped her phone, stumbled to the sink by the wall, and retched her breakfast up into the porcelain.

Nuala

Saturday, 18th November, 2017

Not in the pub, Maggie had said, in case Emma overhears, gets upset.

And nowhere inside the village was private enough, suitable for this kind of talk. Someone else may overhear, Maggie had said, and tell Emma. Poor Emma.

As if Emma was the widow, as if she mattered, as if she had ever been anything to James.

Nuala gripped the wheel of her car, stared at the road, tried to keep calm, relaxed.

She had agreed to drive Maggie out of the village, up to the hill to find somewhere private. Anything to get to the end of this story, to hear the truth at last.

‘Why did you never ask him?’ Maggie shook her head for the fifth time since they had driven away from the pub, watching the shallow rise of the hill from her passenger window. The houses were gone, replaced by the odd stunted sessile oak, the occasional glossy holly.

‘I’d have forced it out of him. If it were my husband, I’d have gotten him drunk, got him to carry on drinking until he’d told all.’

Dark, leafless hedges rose up at the sides of the road, the twigs and branches obscuring the light. From the corner of her eye Nuala could see Maggie’s reflection staring back from the passenger window, the pale grey of her hair stark against the dark foliage outside. Her own features, her brow and eyes visible in the rear-view mirror, were tense as she studied the road.

‘How can you live with someone for seven years and not know why they left home?’

The road lifted and dropped, the blind summit swooping down to the plateau. The wind came from all directions, swirling the fallen leaves into tornadoes, stumps of heather and gorse beaten into submission.

They were at the top of the hills, James’s village in the valley below them, sheep-dotted scrubland to the left, a drop into oblivion on the right. Nuala steered into the wind, forcing the wheels to obey, slowed the car to a crawl.

‘You can’t have known him at all, if you didn’t know about his past. Take the next side-road.’

‘That’s what Lois said; I can’t have loved him, not without knowing him,’ Nuala repeated the words and felt her chest constrict, focused instead on the sounds of the tyres gripping the dirt road.

‘Well, I do love him, I do know him. Did know him.’

The side-road was no more than a dirt track flanked by hazel, blackthorn and the odd stump of gorse.

‘Seems odd, that’s all,’ Maggie said. ‘Stop over there, that gap in the hedge.’

Nuala stopped the car and Maggie jumped out to open a wide, wooden gate, then waved her through. Nuala looked down to see the skin across her knuckles stretched to translucency where she gripped the wheel.

Maggie lumbered back in, the car’s suspension swaying. ‘More peace here, no one to overhear us, no one to go back and tell Emma what I’m about to tell you. If you’d come better dressed I’d have taken you walking, found some privacy up on the hill paths.’ She gestured around them. ‘It was my father-in-law’s, this land. I sold most of it to keep the pub afloat after Tom, my husband, passed, but I kept this bit back so I’ve something to leave to Emma. Land will always be worth more than money, Tom used to say.’

‘Why do we have to be so far out of the village to have this discussion?’ Nuala asked. ‘Why would Emma care?’

‘I don’t want her thinking I’m talking behind her back. She’s sensitive about this business, about anything to do with James.’ Maggie rubbed the scar tissue on her cheek. Nuala could smell the earth on Maggie’s boots from when she opened the gate, manure and rotting leaves from the field outside. ‘As you would know, if you’d ever pushed James to tell you himself. If you’d found out who he really was.’

‘You know, James used to smell of the earth,’ Nuala said. ‘He was a groundsman, his hands smelled like soil, even if he had washed them. In October they would cut back the bracken, burn it in piles once it had dried and use the ash as fertiliser. He used to smell of bonfires in November and that heavy, mossy smell of ferns.’ Her hands were at her face, her index finger in her mouth, teeth gnawing away at the edges. When she drew it back she saw the bright pink slice of a raw wound, blood rising up to the surface. ‘I did know him. He was my husband, I knew my own husband.’

Maggie’s face creased with condescending pity. ‘I’m sure you believe you did.’

Nuala rubbed her neck, needling the skin behind her ear with her fingers. ‘I know that the hat James was wearing in the photo at the pub came from you.’ She thought of it at home on her bedside table, the ultrasound photo tucked inside.

‘I didn’t give it to him—’

‘I know. He stole it. You caught him drinking when he was fifteen. He said he’d never give it back if you told Lois and you said he could keep it, even though it was your late husband’s.’

Tall patches of hay-like grass loomed over the car, the strands brushing against the window in the swirl of the wind, their shadows lashing her thighs.

‘Well, James never had a hat on his head, even in winter.’ Maggie stared into her lap. ‘He could have done with one.’

‘I know he got textbooks every Christmas, never toys. I know Lois gave him Bird’s custard for pudding every Sunday, made with water. I know the holes in his shoes were fixed with cardboard insoles, that when his father died Lois altered the old man’s clothes and gave them to James for his twelfth birthday.’

Nuala could hear the grass thrashing the car, whipping the ground, and beyond it the sound of the wood pigeons’ pitiful repetition. The sound brought back more memories of James, of the hum that escaped with his breath when he found the album of her childhood birthday parties, the pony she was gifted at eight, his face sad and sullen as he told her he’d never had a birthday party as a child, not one and certainly nothing like this, his hand flicking the picture of Nuala’s new pony, a happy birthday hat perched on its head. James’s voice had been sharp and if it hadn’t been for the sad look in his eyes, Nuala would have thought he was jealous. But he didn’t need ponies and parties and gifts to prove his worth. And he certainly wasn’t jealous of her, why would he be? Why would anyone be jealous of her? The thought made him laugh and he did. He did.

No, the photos of her parties reminded him of his mother, led to a rare mention of her, how shit she had been, how she’d done nothing for him, nothing. The first woman in his life to disappoint him.

‘I know that, in the holidays, Lois made him redo the schoolwork he had failed. I know he hardly had any friends because nobody was allowed to play with him.’ She looked to the sky and saw the swirl of pale grey clouds, whiter where the sun tried to break through them, darker where they tempted rain. Thought of James telling her, again, that they would never need anyone else, just each other, no need for outside interference.

‘I know he used to dread the winter because his house didn’t have central heating, because his mother would make him share her bed to keep warm.’

She could hear James again, ordering her never to go there, to just do as he said for once. She wished he was alive, safe at home, warm beneath a blanket or in front of a fire but he wasn’t, he was here with her, waiting in the mud, the wind and grass whipping his frame whilst he stared at her, his face telling her what a fool, what an idiot, she had been not to listen. That she was disappointing him, again.

‘And I know he loved you, Maggie.’ Her chin wavered and she swallowed, tried to remember all

the good things James had told her. ‘You taught him to ride a bike the summer his dad died, you let him into the pub when it was cold, gave him cider to warm him up even when he was too young for it, gave him the cream from the top of the milk and the fat from the bacon, fried to a crisp and wrapped in buttered bread.’ She breathed in, the damp rot of leaves and mud invading her senses. Even with her eyes closed she could see her husband, hear his voice in her head as he told her stories about Maggie, his tone far softer than it normally was.

‘Someone had to watch out for him. He took his father’s death terribly hard, happening, as it did, on the boy’s birthday.’ Maggie stared at her knees, clearly moved by what Nuala had said. ‘I’m surprised he remembered all that.’

‘He told me more about you than anyone else, it’s the reason I came straight to your pub, how I knew I would be safe there with you. He told me,’ Nuala reached out, touched Maggie’s shoulder, waited for the woman to look up before she went on, ‘you were the mother he needed when his own mother failed him. He said you were the mother he wished he had had.’

‘Lois was too young, could barely cope, and her parents would have nothing to do with them. I helped when I could. But then my husband died and I really was in no fit state, I couldn’t even look after my own—’ Maggie stopped, looked out of her window and sighed.

Nuala’s hand was still on Maggie’s right shoulder. ‘I know you can’t hate him, Maggie. You looked after him and he loved you for it. I know that, whatever he did, you loved him too, because seven years later, you still have his photograph on the pub wall, even if you won’t let anyone speak his name.’

‘Did he really say that?’ Maggie asked, her mournful voice tinged with regret. ‘About me being the mother he wished he’d had?’

Nuala nodded, her eyes on James’s phantom in the grass.

The wind was momentarily still, outside quiet. Maggie shifted in her seat. ‘Maybe it’s best you don’t know. I don’t want to tarnish your memories, I know how precious they can be.’

Never Go There

Never Go There