- Home

- Rebecca Tinnelly

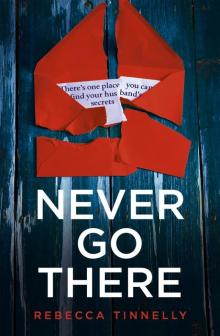

Never Go There Page 2

Never Go There Read online

Page 2

Mouth dry, she turned and followed Maggie up the stairs, telling herself it wasn’t an outright lie, just a fib, that everyone gave a fake name when they went away, it was normal. That it was best, for now, that they didn’t know who she was.

She’d tell them afterwards, when she’d been to see her, explained about him.

And the letter throbbed on in her pocket.

Emma

Friday, 17th November, 2017

The woman had a Burberry bag. Emma had clocked it as soon as she walked in. She’d kill for that bag, for those well-cut black jeans, for the boots, for the jumper, the lot.

The woman had arrived two hours ago, hadn’t been downstairs since, hadn’t asked for any food, no drink. What was she doing up there? And why was she here, out of season, not dressed for walking, nor hunting, clearly not a tourist?

Women travelling solo, complete with designer bags, didn’t come to a place like this. Emma wouldn’t be in a place like this if she didn’t have to be.

She looked into the room from behind the bar, pretending the bag, jeans, boots were on her, pretending she, for once, was an outsider seeing the pub for the first time.

An old man in a gravy-stained cardigan, falling asleep at the fire. Windows that let in a draught, their frames either cracked or warped with damp. Damask armchairs that, a decade after the ban, still smelled of stale cigarettes. A floor that looked dirty, no matter how many times Emma got on her knees and scrubbed her hands red raw on the stains.

A pit. She’d see a pathetic pit not even half full on a Friday night, the main custom coming from a table of twats drinking the cheapest beer on offer, one blond prick, in particular, keeping his back well turned to Emma.

She’d see a glimpse of Emma’s life. Emma’s future.

It was meant to be so much better than this.

What’s her life like, Emma wondered, looking at the slice of light filtering through the floorboards from the guest bedroom above. The woman hadn’t made a sound upstairs, no footsteps on the creaking floorboards, no tap running or water glugging in the chipped sink.

But the light was still on, she must be awake.

What was she doing up there?

Emma looked at the register, the blue-covered exercise book, staring up from its place by the till. Mrs James, she’d called herself.

The name, that name, was a ripple, a shot of adrenaline, bursting from her innards out. Even the penmanship was shaky where Emma had written the name down.

That name. James.

It was a common one.

A coincidence.

But if Emma had been in charge, had been alone when the woman arrived, she would have taken more details. She’d have taken her first name for starters, her address, phone number, written down her debit card details.

Maggie was too desperate for the income, that was her problem. Too eager to keep the charge cash-in-hand, off the books and away from the tax man’s sharp eye. Didn’t care who stayed there, as long as they left their deposit.

But Emma: she would have got enough to Google the woman, find out who she was, where she lived, how she afforded a bag like that one.

Her finger slid over the screen of her phone, one eye on the bar to make sure no one was watching.

Dwelling on Mrs James would get her nowhere, would only bring up memories she’d rather forget. And if she typed that surname into Google, the auto-fill would suggest the rest of a different name, and she wouldn’t do that, search for that. She hadn’t searched that name in months.

She put her phone back down on the counter, noticed the splash of beer on her jeans, the bleach mark on her cheap, black t-shirt. Told herself not to care what people thought of her, a mantra Emma had been repeating since the age of fourteen when she left home (left; as if the choice had been hers) and moved into Maggie’s, her godmother’s, spare bedroom.

At least she had a job, even if it was shit, made her hair stink of rotten fruit and dried yeast. At least she was educated, had A Levels, GCSEs and bloody good ones at that. And so what if her father hadn’t talked to her, properly, sincerely, in the seven long years since he’d blamed her for … for what? Which part of that terrible time had he laid flat down at her feet? She didn’t know. He wouldn’t talk to her and she had no other living parent to ask. But she had Maggie, she wasn’t alone.

What did she care what some blow-in thought of her anyway? But her eye caught the corner of the register again, remembered the name inside.

She looked into the bar, the place she was never meant to stay for so long.

Closed her eyes, clenched her fingers around the edge of the counter, remembered the face, the man, the shitty mess seven years ago that had led her to this point.

‘Beer, ta.’

She opened her eyes, clocked the blond prick at the bar. Plastered a smile on her lips, softened her eyes, said, ‘Of course, I’ll get right on to it.’

She kept the smile there whilst the beer flowed into the glass, her fist tight around the cold, brass lever.

‘You’re looking pale,’ Toby said, leaning over the bar and taking his drink from her hand. ‘You all right?’

Emma looked up from the beer tap, smile still fixed on her face, met his eye, held it. ‘I’m fine; why wouldn’t I be?’

Toby smiled back, had the audacity to look sheepish. ‘I was worried I’d upset you,’ he said.

What a prick.

He lowered his voice, looked behind him at the table of his friends by the window, back to Emma and said, ‘You understand?’

‘There’s nothing to understand.’ Her cheeks were aching with the smile she wouldn’t give up, not for him. ‘I’m over it already.’

He looked relieved, brushed back his blond hair with one hand. Gave her that look, the half-smile that brought out the laughter-lines on one side, made his bright blue eyes crease at the corners.

‘So,’ Toby looked over his shoulder again, made sure no one was watching, ‘you up for tonight?’

‘Up for what, exactly?’ Hands beneath the bar, she picked at her fingers, at the old bleach scars adorning her knuckles.

‘You know,’ Toby said, looked behind him again, moved his arm across the bar and stroked the bare skin on her arm, his touch light and swift, goosebumps spreading from Emma’s wrist upwards.

She looked at him standing there, his childlike blond hair and blue eyes, his breath full of hops. Thought how, two days ago, two weeks ago, a month, she had thought him so damn hot that it hurt.

‘You want to come upstairs?’ she whispered, leaning in. ‘Take the room opposite mine, sneak over once Maggie’s gone to bed?’

She kept her eyes on his, still aware of the chink of light coming through the floorboards above, of the woman upstairs, of the room she had taken, the room Toby had slept in last week. And the week before that.

Toby craned forward, nodded, said, ‘Yeah, let’s do it.’ Licked his lips and Emma thought of his tongue, of his mouth on hers, on her naked body, and shuddered.

She leant in further, her mouth by his ear, just the wooden bar separating their bodies.

‘We’re over,’ she whispered, her breath brushing his earlobe, making him quiver, ‘I deserve better than a fuckwit like you.’

He jumped back, blushed and looked back over his shoulder but none of his friends bothered looking up.

‘Come on, Em,’ he said, louder this time. ‘Don’t be like that.’

‘Like what? Pissed off that you told me we were together, a cute little item, yet you denied me, completely, in front of your friends?’

‘Keep your voice down,’ Toby said, looking backwards again, his friends laughing together, oblivious.

‘See?’ Emma said, laughing to herself, wanted to add, you’re a twat, but it would get her in trouble. ‘Go sit down,’ she told him instead.

She watched him walk back to his table of friends, saw him shrug off her insult, melt back into the conversation.

It was true, she deserved better than this.

/>

Better than a small, crappy pub in the middle of nowhere, nothing to offer her but ignorant locals. Toby was laughing, along with his friends, looking at her and laughing again.

She shouldn’t be here. She should be somewhere else, living a life so very different from this. She shouldn’t be here.

‘Yours, is it? A new one?’

Emma’s ears pricked, head tilted towards the table, listening to Toby and his friends discuss an unfamiliar red car parked in the village. She lifted a pint glass, started polishing it with a cloth, hands occupied to cover her eavesdropping.

‘Not mine,’ said Timmer, a fat ginger lad with a Barbour thrown over his chair. ‘Some grockle’s, most likely.’

Was it hers then, upstairs? There was no car outside the pub, Emma had checked. If it was hers, the woman must have parked somewhere else and walked over. If she’d parked outside, Emma would have taken the details, registration, gone online to see what she could find.

‘Why the fuck are they visiting Shore Road?’ asked Robbie Burrows, son of the old man half asleep by the fire.

The glass dropped from her hands, smashed, all the men looked up, stopped talking.

Shore Road.

Mrs James.

Emma dropped below the bar, leant her back to the counter, bottom on the floor, pretended to clean up but she could barely move, barely breathe.

She had only been half serious, suspecting a link. Had thought it a coincidence, nothing more. But the location, the name, the possibility started seeping in, turning her blood cold even though her cheeks burned.

The memories started flooding in, her mind ticking backwards, ignoring the customers, Edward Burrows, the old man sitting by the fire, calling out, ‘You all right?’

She heard footsteps on the stairs, Maggie coming up from the cellar. Thank God, Emma needed to get out, needed to walk the memories away, leave the bar to her godmother for the night.

Emma had always known that one day, this would happen.

Maggie

Friday, 17th November, 2017

Maggie gripped the gas canister between her hands, the cylinder thicker than a man’s neck. She lifted it up without a groan of complaint or a struggle and hefted it to the wall, clicking it securely in place. Her arms tingled from their load, reminding her of her age, reminding her, too, of her strength despite it.

A crash from upstairs, a glass breaking.

A thump on the floor, directly above Maggie’s head, as though someone had slumped to the ground by the till.

Emma.

Maggie looked around her; the last of the barrels not yet hooked up, the letters strewn on the third step down and the landline phone, still warm from where her hand had clutched it, lying face up beside them.

She couldn’t leave it like this. Emma might find them, the typed letters received in the post, Maggie’s reply handwritten and ready to send. She couldn’t work that computer upstairs, not even after Emma tried giving her lessons. Besides, a handwritten note was more sincere, more likely to tug at the heartstrings, draw sympathy. And if she typed it up there was a chance that Emma might see.

And she couldn’t let that happen.

A curse from upstairs, slurred around the edges but concerning nonetheless. What was the cause of the smash, the thump? Was it the customers upstairs getting rowdy? She needed to get up there, help her goddaughter.

Maggie picked up the letters, knees groaning as she bent them, begging her, please, to lose weight. She stuffed the sheets of paper in a plastic folder, slid the folder between the barrels at the back.

The phone she left in its place. There was a chance Arthur might call back, given that she’d just hung up on him. She couldn’t risk Emma hearing the landline ring, didn’t want her picking up the call and hearing her father’s voice on the end of the line.

‘What choice do you have, Maggie?’ His words still rung in her ears, her cheek and scar hot from the pressure of the handset. She had looked at the letters from the bank, her name, Mrs Bradbury, on the top line of each, cursed the fact that she shared the same name with the man on the phone, her husband’s dark-hearted cousin.

Maggie headed up two steps at a time, out of breath at the top and pulse thrumming. Sixty-five next June. She was getting too old for all this.

She spread her hands on the wall by the cellar door, leaning into them to catch her breath.

A cold, wet slick on her palm, her hand reeking of mould. Damp.

The last thing she needed. It already had its grip on the rooms upstairs, the hallway carpet boggy and wallpaper black. If it was down here, too, if it reached the barrels, the stock – she closed her eyes, wouldn’t think of that, she’d do something, fix it. But the letters downstairs, the empty bank account, overdraft, mortgage, the loan she hadn’t the money to repay. How could she fix anything?

‘Emma?’ She opened her eyes, saw her goddaughter, sitting bottom down on the floor behind the bar, splinters of glass all around her.

‘I’m all right,’ Emma said, not trying to get up.

‘What happened?’ Maggie rushed to her through the archway cut out in the kitchen’s plasterboard wall. ‘Someone’s upset you, who was it?’ She looked over the bar at the room. Edward Burrows, the old man, was sitting upright in his chair by the fire, his hands raised as if to say, ‘Don’t ask me.’ His son Robbie and his friends were sitting at the table nearest the door, shrugging in unison when Maggie looked over.

Emma shook her head, held on to Maggie’s sleeve, pulled herself to standing, her face pale. Her mouth was set firm, eyes hard, but Maggie could tell, from the way her goddaughter’s hands were shaking, that something had upset her more than she was willing to show. She lifted the hatch, stepped into the bar, one hand squeezing Emma’s shoulder.

‘Ignore them,’ she whispered, still thinking it was a customer’s fault, that someone had said something, some piece of gossip that had inadvertently upset her. Talked about her father, perhaps. Some new business deal raising eyebrows, or perhaps an old grudge. Memories were long in these quiet, cut-off places, Maggie knew. She only hoped, for Emma’s sanity, that they hadn’t been talking about the girl’s own past.

She looked down at Emma’s phone, lying screen-up on the counter. The screen said No Connection but the search bar was open. She’d been looking for something again. Looking for someone.

‘I always ignore them.’ Emma offered her a smile, lifted the phone and slipped it into the pocket of her jeans.

‘Go put the kettle on,’ Maggie told her, squeezing her shoulder again. ‘I’ll sort this lot.’

She should find out what had happened, who had said what and, if necessary, bar the lousy toad responsible, set an example. But she could see the table full of young, thirsty customers, the empty glasses waiting to be refilled, the wallets of cash resting among them ready to pay, thought of the bank statement she’d hidden in the cellar, the side of her face still hot from where the phone was pressed to it, ‘what choice do you have?’ playing again in her ear.

‘That true, what Timmer said?’ A man’s voice drifted over from the fireplace. Maggie turned to see the bald head of Edward, Robbie’s father, visible above the top of the damask armchair.

It was out of character for the man to comment on others’ conversations, to draw Maggie into talking at all. Normally his vigil by the fire was a silent one, drinking until nine o’clock when he would stumble back home to his wife of forty-five years in the terraced house they rented (on the cheap, Maggie suspected) from Arthur. The change in Edward made Maggie stop, pay him attention.

‘Is what true?’ she asked, rubbing the mark on her cheek where, years ago, the scar tissue had turned keloid from picking.

‘There’s a car out there that no one recognises,’ he said, hands hugging his dimple-glass tankard. ‘I wouldn’t care, only it’s parked right outside Lois’s front door.’

News to Maggie, but she withheld her surprise, kept her face neutral to keep Edward talking. The only newcomer sh

e had seen in the village that day was the woman now resting upstairs. But she had said nothing about a car, and Maggie couldn’t be sure it belonged to her at all. She kept quiet, not sure yet what Edward was trying to tell her.

‘Has Lois asked someone here, do you think?’ he said.

Maggie thought of the stranger in the room upstairs, the way she had gritted her teeth, called herself stupid for something as simple as dropping a purse. If that was her car, if she was here to see Lois, then Lois would eat her alive. ‘I hope not,’ she said.

‘So do I.’ Edward looked up, his face dappled with age spots that matched the gravy marks on his white shirt. ‘She’s no business dragging strangers here.’

‘Tea, Mags,’ Emma called from the bar, placing a mug on the sleeper before slipping back out to clean up. Maggie hid the mug behind the till on the counter, cooled it down with a capful of gin.

‘It’s probably nothing,’ Maggie said, sitting down by the fire with Edward. She could sit down for five minutes, rest her back and her arms from the strain of the barrels. Rest her head from the ache of bank statements. ‘I doubt whoever owns the car means any trouble. It’s too quiet around here, that’s the problem. People are eager to read drama into the mundane.’

The woman upstairs hardly seemed a trouble maker. Her clothes were too neat, her manner too meek. But then again, there had been something in her eyes, when she’d given her name, handed Emma the tenner deposit. Was she a lawyer, perhaps? Or a reporter? But what story could she be looking for, way out here? And why now? Nothing of significance had happened in years, no scandal, no showdowns, nothing grisly. The last untimely death in the village had been that of Emma’s stepmother, Elaine, nearly a decade before – and even though it had broken Emma’s heart, losing her stepmother like that, it hadn’t made the local papers. No, the woman couldn’t be a journalist.

Edward shook his head, his knuckles white against the pint glass, his eyes staring into the fire. ‘Arthur won’t be happy if Lois has been talking out of turn to some blow-in,’ he said, his mouth closing tightly before any more words could escape. He was Arthur’s friend as well as his business secretary, predominantly involved in collecting the rent from the three local farms and ten houses that Arthur owned. Edward had run so many errands for that man, over the years, that Maggie was certain he knew all of Arthur’s tricks for getting his way, as well as a few of his darker secrets.

Never Go There

Never Go There